Over a year into the Coronavirus pandemic, it seems we have sufficiently experienced the virus, and its accompanying hardships, to begin to judge it from a different lens – one of retrospect and reflection. Viewing the pandemic we are currently faced with in the context of that in 1918, it is clear that although we have come a long way in the last century, viral diseases, able to jump the barrier of animal to human, still remain a severe and real threat to public health, and we appear to have failed to learn from our past mistakes. Both came in waves, and in both cases human society struggled to control the spread. This was because the realities of life, the war in 1918, and the economy in 2020, were at odds with the necessity of containment. Likewise, the actions of a few individuals either improved, or worsened the situation.

In 1918, Sir Arthur Newsholme, as a leading public health expert, was responsible for Britain’s response to the outbreak. However, he failed to follow the advice of leading health experts such as James Niven, Manchester’s Medical Officer of Health, who understood the immediate necessity of enforcing social distancing measures, urging schools and businesses to close. Newsholme’s actions, or rather failure to intervene more vigorously, cost thousands of lives, and may be seen as part of the reason why the pandemic, that actually originated in Kansas, earned its common name – the ‘Spanish Flu’. Just before breakfast on the morning of March 4, Private Albert Gitchell of the U.S. Army reported to the hospital at Fort Riley, Kansas, complaining of cold-like symptoms (sore throat, fever and headache). By noon, over 100 of his fellow soldiers had reported similar symptoms – marking the beginning of the outbreak, believed to be the first of the historic influenza pandemic. However, with the world plunged into the Great War, the virus spread rapidly through the U.S., and in turn the whole world. The story of the Leviathan, a troopship that on 29 September carried 2,000 crew and 9,000 troops from New York to Brest, France, is a microcosm of how soldiers converging in Europe brought the virus with them. The voyage would prove to have the worst in-transit casualties of the deadly second wave of the Spanish flu: by the time she arrived at Brest on 8 October, 2,000 were sick, and 80 had died. It was only when the virus reached Spain, a country not engaged in an all-consuming war effort, that news of the virus hit the headlines, informing the world of the scale of the horror unfolding as international governments continued to refuse to acknowledge the threat. Then, as now, disparities in press coverage act as a reflection of differing responses to the virus, and the speed with which it can spread.

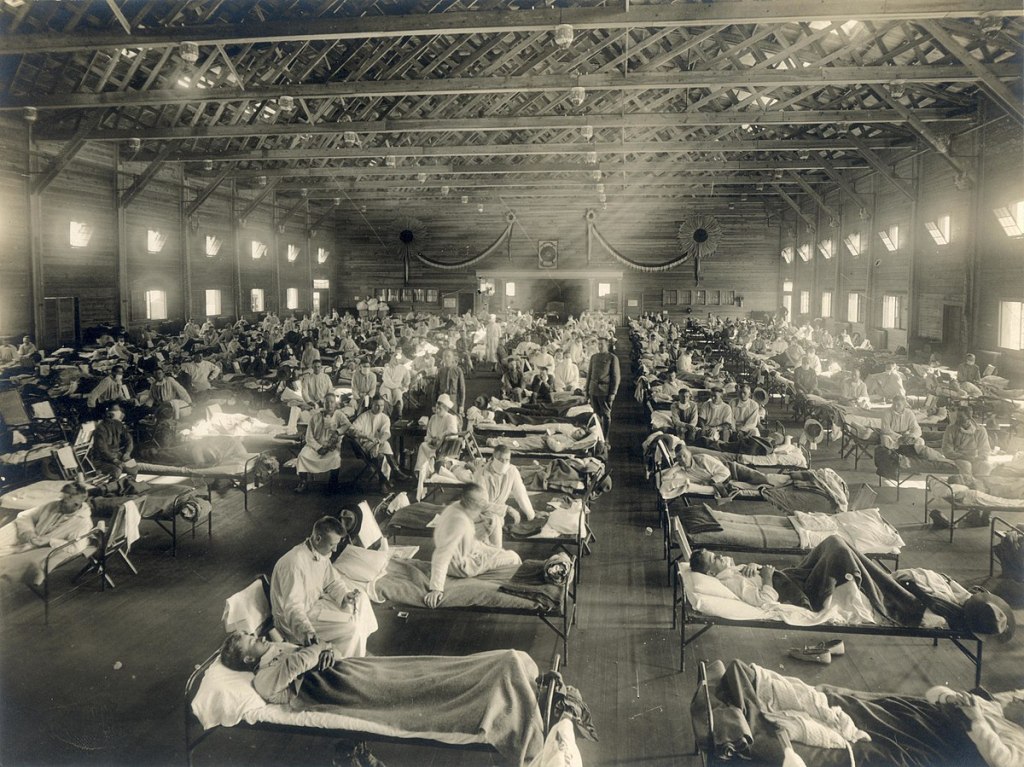

But flu does not just travel by ships anymore, it travels by planes and trains. In a world that appears to be continually shrinking, the potential for the Coronavirus to travel further and faster is an alarming reality. Thanks to modern air travel, Covid-19 was able to travel around the globe at an unprecedented rate. When the virus reached our shores balancing health and economic concerns proved a constant battle, and it took the UK government weeks to accept that lockdown was a necessity, and would be a reality for a long time. Similarly, in 1918, Sir Arthur Newsholme, choosing to prioritise the war effort over the health of the nation, belittled the serious threat the virus posed, refusing to accept the necessity of introducing measures to control the virus. Consequently, at least 228,000 people were killed by the virus in the United Kingdom alone. In comparison, 61, 245 have died as of 7 December 2020, a testament to the enormous improvements in medicine: where Dr. Basil Hood (the doctor who ran St. Marylebone Infirmary in London) had almost no effective medicines to combat the flu, restricting him and his nurses to providing mostly palliative care, and William Welch (an American physician at the time) was unaware that the virus had originated in wild water fowl, we now we have a much greater understanding of the virus.

In examining the two pandemics we have faced over the last century, it is evident that while history doesn’t always echo, it does indeed rhyme. Although we can study history and search for correlations in events, ultimately it is the constant presence of human nature that allows our actions in times of difficulty to be predictable, even if disappointing.